A lot of people have been insisting that we must be incensed by Elliot Rodger's killing spree not only because of the death toll, but because he was a misogynist. I got to thinking about this and read his manifesto (my highlighted version is here). Here goes--my thoughts about why he did it, and the role played by misogyny.

Starting at puberty Rodger begins to worry that other boys/men get to have sex with beautiful girls/women, and he doesn't. Life is horribly, horribly unfair, he thinks. The manifesto contains endless passages expressing anger against men, and endless passages experessing longing for women. Even when he expresses hatred for women, throughout most of the manifesto it's not hatred because they're women, or because they're inferior. He hates women for not giving him sex, just as he hates men for not giving him friendship. These hatreds are parallel, one no more driven by gender bias than the other.

The turning point in the manifesto is pg. 88. This is when he starts to become violent and realizes he could become very violent. Twice he witnesses couples making out, and then furiously throws his coffee at them. He doesn't feel furious because women are crap or expendable or "just things," but because life feels unfair. He is furious that women are unattainable for him, but attainable for others. He cannot do anything or go anywhere without noticing couples and resenting his inability to attain the pleasures of sex and love. He even has to drop classes he's taking because he's so disturbed by couples and attractive women. He is totally obsessed.

For a while he gets the idea he can solve the problem by dressing well or winning the lottery and thereby attracting a woman, but of course that doesn't work. After additional minor attacks on couples and groups of women he decides it's time to start preparing for the Day of Retribution, when he will punish everyone for his sufferings. He buys a gun. The planning and the gun purchase are not preceded by sexist or misogynistic ravings, but by the very same obsessions that fill the manifesto--it's not fair, I long for girls, but other, less worthy guys always get the girls. He seeks retribution because that's the only way he can think of to rectify this terrible unfairness.

Rodger shows little sign of being particularly sexist for most of the manifesto, but he does have a very warped idea about male-female relationships. He thinks getting sex is some kind of a reward for being an impressive man. Having a woman at your side tells everyone "This guy is great!" Not having a woman says "This guy is a loser!" He fails to understand the connection between friendship and sex, and thus cannot start down a path that could lead to sex.

Starting on p. 117 things change and he starts fixating on his hatred of women. Prior to this, I think expressions of hatred for men are far more numerous. He is desperate to explain why women don't feel attracted to him. He can't bear to think it's because of something about him, so he finds fault with women. Now he writes a paragraph of extreme misogyny. But it is very late in the day. This comes after the plan for retribution has been made and the first gun has been purchased, and after hundreds of expressions of anger toward men as well as women, and after hundreds of complaints about life's unfairness.

After the misogynistic paragraph, he quickly comes back to his standard theme: "Women must be punished for their crimes of rejecting such a magnificent gentleman as myself. All of those popular boys must be punished for enjoying heavenly lives and having sex with all the girls while I had to suffer in lonely virginity." (p. 118) And: "I wanted to kill as many attractive young couples as I possibly could." Which is not to say there is never any gender-directed hatred: "My hatred of the female gender could grow no stronger." But he is angry at women because they haven't chosen him for sex, and that is all.

Here's what he says about the roommates he murdered: "These two new ones were utterly repulsive, and one of them had a very rebellious demeanor about him....I knew that when the Day of Retribution came, I would have to kill my housemates to get them out of the way. If they were pleasant to live with, I would regret having to kill them, but due to their behavior I now had no regrets about such a prospect. In fact, I'd even enjoy stabbing them both to death while they slept." (p. 128) Yes, he hates these guys too, not only the sorority women he plans to kill.

Here's a sentence about his sister's boyfriend, toward the end. It sums thing up pretty well: "It is such an injustice. The slob doesn't even have a car, and he is able to get girlfriends, while I drive a BMW and get no attention from any girls whatsoever." (p. 129) But then, there is this misogynistic statement about his mother: "But then again, my mother is a woman, and women are all mentally ill." (p. 130) So his anger does occasionally well up into misogyny.

The final passages include fantasies of sadistically killing "everyone" and fantasies of killing women in particular. "I will punish all females for the crime of depriving me of sex." (p. 132) There's nothing in here about how all women are for sex. He's not saying everyone should get to have sex with any women they want. The complaint is that women wanted to have sex with other men, not with him. It was unfair. He does want to kill others, not just attractive women: "I can only imagine how sweet it will be to ram the SUV into all those groups of popular young people..." (p. 142)

But then (yes) there are also misogynistic tirades. On p. 136 he writes about abolishing women, putting them in concentration camps. This is around where he also calls himself a god. He's days away from committing mass murder. To my mind the anger and sense of injustice that's filled his head for years and years have now generated both an extreme misogynistic fantasy about women and a plan for mass murder and a lot of other lunacy. The anger came first and had multiple effects--the misogynistic tirade and other strange thoughts, and the rampage. The misogyny at the end isn't what made him plan to commit murder or carry out the plan.

What you can learn from this manifesto is that one source of murderous anger is the sexual angst of unsuccessful men. If that is right, then the feminist response we've seen (see here and here) invites us to focus on the wrong thing: the widespread problem of overly aggressive boys and men who hit on women, grab at them, commit date rape -- the usual excesses of aggression. Elliot Rodger was a very passive boy/man until his "day of retribution." Yes, yes, of course, he killed a lot of people, which is very aggressive. But the state of mind that led up to this was one of totally passive dysfunctionality. This is a guy who didn't harass girls, didn't grab butts, didn't impose himself on anyone. To get women's attention he tried to win the lottery over and over again, and bought himself fancy clothes. He wanted the flattery of receiving a woman's attention.

Of course the misogynistic passages of this manifesto are revolting. In fact, they're so revolting there's no way it can be true that Rodger got these ideas from the culture, as some commentators have said. Right beside the misogynistic passages about putting women in concentration camps (p. 136, close to the end of the manifesto) there are passages about flaying people, cutting their heads off, slaughtering them by the hundreds. Rodgers has completely fallen apart by this point. He's exploding in rage. By reading the manifesto, you can see what brings him to this point, and it's not immersion in a sexist culture.

Moral of the manifesto: beware the shy, passive guy on the sidelines. I think that's been the moral after many of these mass killings. The question is: what to do about it?

5/30/14

5/28/14

Vaccine Refusers

Most vaccine refusers seem to fall into four groups:

It's the You-first refusers that are interesting, to my mind. Thinking about them, you have to open the "social ethics" toolbox, maybe taking out the prisoner's dilemma, the tragedy of the commons, Kant's categorical imperative, the voter's paradox, the social contract, questions about the morality of freeriding, etc.

It's the You-first refusers that are interesting, to my mind. Thinking about them, you have to open the "social ethics" toolbox, maybe taking out the prisoner's dilemma, the tragedy of the commons, Kant's categorical imperative, the voter's paradox, the social contract, questions about the morality of freeriding, etc.

But who thinks like a You-first refuser? Aren't real world vaccine refusers all in groups 1 and 2? In fact, a popular author outright welcomes his readers to be You-first refusers. Here's a delicious/horrifying passage from The Vaccine Book, by Robert Sears, MD.

I do "fault parents who think vaccines are too risky and decide to put their own kids first." I don't think parents "do, and should, have the right to decline vaccination"--if he means a moral right. I'm not even sure parents should have a legal right. But how exactly to make the case? The passage is interesting and challenging because it's not immediately obvious how best to respond. Or rather--you can come up with a roughly right response pretty fast, but it's not obvious what is the exactly right response.

Back to work....

- Conscientious Refusers--people who reject all vaccination, like conscientious objectors in wartime reject all fighting. They usually have religious reasons.

- Critical Refusers--people critical of mainstream science and medicine. They will go on thinking vaccines cause autism (for example) no matter how many studies show otherwise.

- Doing/allowing Refusers--they see a problem with doing something that stands a chance of causing serious side effects, but see no problem with allowing a child to be infected with a vaccine-preventable disease. Unlike those in group 1, they would accept a vaccine with no associated risks.

- You-first Refusers--people who think enough other people are vaccinating their children so that they don't have to. In the early days of a vaccine, when herd immunity doesn't exist yet, they will vaccinate their children. In the late days, when they think herd immunity protects their children sufficiently, they opt out.

It's the You-first refusers that are interesting, to my mind. Thinking about them, you have to open the "social ethics" toolbox, maybe taking out the prisoner's dilemma, the tragedy of the commons, Kant's categorical imperative, the voter's paradox, the social contract, questions about the morality of freeriding, etc.

It's the You-first refusers that are interesting, to my mind. Thinking about them, you have to open the "social ethics" toolbox, maybe taking out the prisoner's dilemma, the tragedy of the commons, Kant's categorical imperative, the voter's paradox, the social contract, questions about the morality of freeriding, etc.But who thinks like a You-first refuser? Aren't real world vaccine refusers all in groups 1 and 2? In fact, a popular author outright welcomes his readers to be You-first refusers. Here's a delicious/horrifying passage from The Vaccine Book, by Robert Sears, MD.

Back to work....

5/21/14

Deadly Choices

This is a superb book--full of information about infectious diseases, the impact of vaccination, the history of vaccination resistance, the autism controversy, and also some very interesting passages about vaccination ethics and the tragedy of the commons. Plus it's very readable and succinct. Highly recommended!

5/20/14

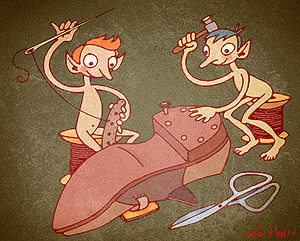

The Elves and the Cobbler

Here's a scenario from Garrett Cullity's article "Moral Free Riding"--

The Enterprising Elves

On the first day in my newly carpeted house, I leave my shoes outside. In the morning I am delighted to find they have been extraordinarily well repaired. I am less delighted when I receive the bill. (p. 10)

This is supposed to be the same type of situation as Robert Nozick's radio thought experiment, which is meant to show there's not always an obligation to pay for benefits nonvoluntarily received.

I say "Right" about this scenario--I don't have to pay the elves--but it seems to me that outright requesting benefits is more than what's needed for there to be an obligation to pay. Consider this continuation of the story of the elves:

The Enterprising Elves and the Cancelled Cobbler

After putting on my shoes and tossing out the bill, I stroll to my cobbler's shop and cancel my monthly shoe repair appointment.

That seems to change things. If I were indifferent to the elves' services and had no monthly plan with the cobbler, I could indeed toss out the bill and never look back. But in fact I welcome their services. Now at this point in the story, it's hard to say I have to pay for the elves' work. Should I pay the elves even though they invaded my cobbler's turf? Should I pay my cobbler, even though he didn't repair my shoes? But consider this:

The Elves Come Back

A month has passed and as usual I leave my shoes outside my door. The elves once again repair my shoes. I no longer have a standing appointment with my cobbler. Once again I toss out the bill.

To my my mind, now the unrequested repairs do have to be paid for. True, I didn't request the repairs, but I welcomed them and my behavior shows I'm counting on the elves to show up. If I'd really wanted to avoid the obligation to pay the elves, I would have had to keep my shoes inside. If I couldn't do that--remember the carpets--then I needed to show I was not counting on the elves by maintaining my appointments with the cobbler and paying his bills. But it just can't be that I may continue to receive the repairs, having arranged my life accordingly, but I don't have to pay for them.

Extrapolation to vaccination ethics ... well, long story. We'll save that for another day.

The Enterprising Elves

On the first day in my newly carpeted house, I leave my shoes outside. In the morning I am delighted to find they have been extraordinarily well repaired. I am less delighted when I receive the bill. (p. 10)

This is supposed to be the same type of situation as Robert Nozick's radio thought experiment, which is meant to show there's not always an obligation to pay for benefits nonvoluntarily received.

I say "Right" about this scenario--I don't have to pay the elves--but it seems to me that outright requesting benefits is more than what's needed for there to be an obligation to pay. Consider this continuation of the story of the elves:

The Enterprising Elves and the Cancelled Cobbler

After putting on my shoes and tossing out the bill, I stroll to my cobbler's shop and cancel my monthly shoe repair appointment.

That seems to change things. If I were indifferent to the elves' services and had no monthly plan with the cobbler, I could indeed toss out the bill and never look back. But in fact I welcome their services. Now at this point in the story, it's hard to say I have to pay for the elves' work. Should I pay the elves even though they invaded my cobbler's turf? Should I pay my cobbler, even though he didn't repair my shoes? But consider this:

The Elves Come Back

A month has passed and as usual I leave my shoes outside my door. The elves once again repair my shoes. I no longer have a standing appointment with my cobbler. Once again I toss out the bill.

To my my mind, now the unrequested repairs do have to be paid for. True, I didn't request the repairs, but I welcomed them and my behavior shows I'm counting on the elves to show up. If I'd really wanted to avoid the obligation to pay the elves, I would have had to keep my shoes inside. If I couldn't do that--remember the carpets--then I needed to show I was not counting on the elves by maintaining my appointments with the cobbler and paying his bills. But it just can't be that I may continue to receive the repairs, having arranged my life accordingly, but I don't have to pay for them.

Extrapolation to vaccination ethics ... well, long story. We'll save that for another day.

5/19/14

When is freeriding wrong?

One reason we ought to vaccinate children is because otherwise we'd be receiving the benefit of other kids' being vaccinated for free--we'd be freeriders. On top of that, we may have to vaccinate simply to protect our own children or for altruistic reasons--to protect vulnerable people the child comes into contact with. But if you are a member of a society with high rates of vaccination, the "No freeriding!" reason will be a major one, at least with respect to many standard childhood vaccinations (on the various ethical issues raised by different vaccinations, see this very useful article). So it's important to figure out when freeriding is morally wrong--and whether it's wrong when vaccination refusers do their refusing.

Certain scenarios make it pretty clear that freeriding isn't always wrong. Robert Nozick's example of the freeriding group radio refusenik is a nice example of permissible freeriding. Generally speaking, it just can't be that an aggressive neighborhood association can saddle me with endless obligations to contribute to their collective schemes. Likewise, an enthusiastic PTA may generate any number of projects that do have benefits for all, but we wouldn't want to say they have the power to make it obligatory for parents to pitch in on all of these things. The basic intuition here, I think, is that there's a difference between receiving benefits you requested and receiving benefits that come unbidden. But what about these unbidden benefits? There are cases and then there are cases.

Here are three that involve individual rather than collective benefits, but I think they're illuminating nevertheless:

If benefits must be requested for you to have to pay for them, then you have to pay only in Case #2. My intuition, though, is that you have to pay in both Case #2 and Case #3. You didn't request the subscription you go on enjoying in Case #3, but your actions are tantamount to requesting it. Your actions show you'd be prepared to pay, if it came to that. After all, you're on standby, ready to do differently, if you're ever threatened with losing the benefit. You paid for a subscription before you got lucky, so presumably you'd pay again, if the free copies stopped arriving.

This analysis carries over pretty well to cases where one benefits from a collective project. I don't have to support the neighborhood radio show because, though I may enjoy it, I'm not on standby, ready to do differently if my non-participation threatens the show. I'm prepared for the show to fail. Some goes for many (but not all!) PTA projects. I'm not on standby, ready to do any differently. Vaccination is different. Many refuseniks would presumably participate, if their non-participation threatened the immunity of their child's school. The vaccination refusenik is therefore not just a benefitter from but a welcomer of immunization. In fact, more than that: the refusenik is poised to participate more, if others participated less.

Now, collective projects are more puzzling. The magazine subscriber in Case #3 is prepared to pay, if paying is needed to keep the magazine coming. He's on actual standby, ready to take out his wallet. The vaccination refusenik is not on actual standby, but only on "hypothetical" standby: she would be prepared to vaccinate, if (contrary to fact) that were ever needed to preserve herd immunity. Arguably, though, the same moral flaw is on display in both cases: putting yourself on mere standby, while others actually pay for a benefit you value, makes you an exploiter of actual payers.

If you're not on standby, but ready to see an unrequested product disappear or a collective project fail, that's another matter. We might still judge you harshly--for having terrible judgment about the worth of the project--but you wouldn't be a freerider. You might even be something worse, but you wouldn't be a (bad) freerider.

Certain scenarios make it pretty clear that freeriding isn't always wrong. Robert Nozick's example of the freeriding group radio refusenik is a nice example of permissible freeriding. Generally speaking, it just can't be that an aggressive neighborhood association can saddle me with endless obligations to contribute to their collective schemes. Likewise, an enthusiastic PTA may generate any number of projects that do have benefits for all, but we wouldn't want to say they have the power to make it obligatory for parents to pitch in on all of these things. The basic intuition here, I think, is that there's a difference between receiving benefits you requested and receiving benefits that come unbidden. But what about these unbidden benefits? There are cases and then there are cases.

Here are three that involve individual rather than collective benefits, but I think they're illuminating nevertheless:

Case #1 - The Accidental Subscription. Suppose due to a mistake somewhere, you wind up being sent a subscription to Rolling Stone. You receive it every week and read it, not bothering to contact the magazine to let them know their error. (Real life example!)

Case #2 - The Requested Subscription. In this scenario you get Rolling Stone because you requested it.

Case #3 - The Double Subscription. In the third case, you have a requested subscription, and then an accidental subscription starts to arrive. You think "Lucky me!" and cancel your paid subscription. You continue enjoying the accidental subscription without paying for it.

If benefits must be requested for you to have to pay for them, then you have to pay only in Case #2. My intuition, though, is that you have to pay in both Case #2 and Case #3. You didn't request the subscription you go on enjoying in Case #3, but your actions are tantamount to requesting it. Your actions show you'd be prepared to pay, if it came to that. After all, you're on standby, ready to do differently, if you're ever threatened with losing the benefit. You paid for a subscription before you got lucky, so presumably you'd pay again, if the free copies stopped arriving.

This analysis carries over pretty well to cases where one benefits from a collective project. I don't have to support the neighborhood radio show because, though I may enjoy it, I'm not on standby, ready to do differently if my non-participation threatens the show. I'm prepared for the show to fail. Some goes for many (but not all!) PTA projects. I'm not on standby, ready to do any differently. Vaccination is different. Many refuseniks would presumably participate, if their non-participation threatened the immunity of their child's school. The vaccination refusenik is therefore not just a benefitter from but a welcomer of immunization. In fact, more than that: the refusenik is poised to participate more, if others participated less.

Now, collective projects are more puzzling. The magazine subscriber in Case #3 is prepared to pay, if paying is needed to keep the magazine coming. He's on actual standby, ready to take out his wallet. The vaccination refusenik is not on actual standby, but only on "hypothetical" standby: she would be prepared to vaccinate, if (contrary to fact) that were ever needed to preserve herd immunity. Arguably, though, the same moral flaw is on display in both cases: putting yourself on mere standby, while others actually pay for a benefit you value, makes you an exploiter of actual payers.

If you're not on standby, but ready to see an unrequested product disappear or a collective project fail, that's another matter. We might still judge you harshly--for having terrible judgment about the worth of the project--but you wouldn't be a freerider. You might even be something worse, but you wouldn't be a (bad) freerider.

5/16/14

"Soft Atheism"

Philip Kitcher hits many nails on the head. I like what he says about the reason to be skeptical of all religious beliefs. Yes, this really is "the most basic reason for doubt" (or one of them):

I also like what he says about rejecting religious doctrine while retaining the achievements of "religions at their best":The most basic reason for doubt about any of these ideas is that (when you understand words in their normal, everyday senses) nobody is prepared to accept all of them. Even if you suppose that Judaism, Christianity and Islam share some common conception of a divine being, the Hindu deities are surely different, the spirits and ancestors of African and Native American religions different again, and that’s before we get to Melanesian mana or the aboriginal Australian Dreamtime. It’s very hard to think that every one of these radically different conceptions picks out some aspect of our cosmos.So asserting the doctrines of a particular religion, or family of religions, requires denying other contrary doctrines. However, when you consider the historical processes underlying the doctrines contemporary believers accept, those processes turn out to be very similar: Long ago there was some special event, a revelation to remote ancestors. Religious doctrine has been transmitted across the generations, and it’s learned by novice believers today. If the devout Christian had been brought up in a completely different environment — among aboriginal Australians or in a Hindu community, say — that person would believe radically different doctrines, and, moreover, come to believe them in a completely parallel fashion. On what basis, then, can you distinguish the profound truth of your doctrines from the misguided ideas of alternative traditions?

To sum up: There is more to religion than accepting as literally true doctrines that are literally false. Humanists think the important achievements of religions at their best — fostering community, articulating and supporting values — should be preserved in fashioning a fully secular world. That secular world ought to emerge from a dialogue between humanism and refined religion, one in which religion isn’t thrown on the rubbish heap but quietly metamorphoses into something else."Soft atheism," he calls this.

5/15/14

Nozick's Group Radio Thought Experiment

Here's a fun thought experiment from Anarchy, State, and Utopia (Robert Nozick), with a few variants at the end:

Do I have to take my turn and produce a radio show? Surely not. We can't be lassoed into obligations that easily--just because some group of people decides to jointly bring about a public benefit.

My thought is: OK, I agree with Nozick about that scenario--you don't have to produce the radio show on your appointed day. But what's going on here, and how is this different from other cases in which you are a nefarious freerider for refusing to contribute to a joint enterprise you benefit from but didn't request or initiate?

Do I have to take my turn and produce a radio show? Surely not. We can't be lassoed into obligations that easily--just because some group of people decides to jointly bring about a public benefit.

My thought is: OK, I agree with Nozick about that scenario--you don't have to produce the radio show on your appointed day. But what's going on here, and how is this different from other cases in which you are a nefarious freerider for refusing to contribute to a joint enterprise you benefit from but didn't request or initiate?

5/14/14

A Vaccination Antinomy

Background: Mary and her daughter Violet live on an island with a vigorous voluntary vaccination program. There is nearly 100% compliance, so the population has herd immunity against serious disease X. There are periodically a few immigrants who may carry X, enough to necessitate continuation of the vaccination program. But not enough to destroy herd immunity. The rare refusers don't vaccinate because their children have special medical problems, but Mary isn't in that category. Vaccination records are confidential. The public at large won't know what Mary decides to do.

Here's an argument that Mary should vaccinate Violet. To do otherwise is to unfairly freeride on the other citizens. After all, Mary does believe in the vaccination program and does desire its benefits. She is only contemplating not vaccinating Violet because the others have vaccinated their children. If she goes through with it, she will be taking advantage of everyone else. She will be making an exception of herself, acting as she would not want others to act.

Here's an argument that Mary shouldn't vaccinate Violet. The vaccination is painful, and also poses slight risks. So Mary has to be able to justify the harm she would do to Violet. But she can't. We may harm our children a little or even a lot, to prevent a more serious harm to them. We may harm them a little, to prevent a very serious harm to others. But this case fits neither description. Having her vaccinated would not benefit Violet, since she's already immune to X. It wouldn't benefit anyone else either, since the whole population is immune. It wouldn't even benefit others by encouraging them to keep vaccinating their children, since records are confidential--no one will know if she doesn't vaccinate.

Note: in the real world, people aren't caught in this bind. We don't know there's herd immunity against any particular disease. We can always justifiably think vaccinating a child has some chance of benefitting both the child and others. (And by the way, my own children did receive all the routine vaccinations plus others.)

The scenario isn't real, but it also isn't far-fetched. People could be sure their community has herd immunity against X, and it seems to me these two arguments would genuinely compete for our attention in such a situation. Though I initially lean toward argument #1, it does strike me as strange for a parent to have a child jabbed, in the full knowledge that this is "for fairness" and without benefit to the child or anyone else. Thus: puzzlement.

Here's an argument that Mary should vaccinate Violet. To do otherwise is to unfairly freeride on the other citizens. After all, Mary does believe in the vaccination program and does desire its benefits. She is only contemplating not vaccinating Violet because the others have vaccinated their children. If she goes through with it, she will be taking advantage of everyone else. She will be making an exception of herself, acting as she would not want others to act.

Here's an argument that Mary shouldn't vaccinate Violet. The vaccination is painful, and also poses slight risks. So Mary has to be able to justify the harm she would do to Violet. But she can't. We may harm our children a little or even a lot, to prevent a more serious harm to them. We may harm them a little, to prevent a very serious harm to others. But this case fits neither description. Having her vaccinated would not benefit Violet, since she's already immune to X. It wouldn't benefit anyone else either, since the whole population is immune. It wouldn't even benefit others by encouraging them to keep vaccinating their children, since records are confidential--no one will know if she doesn't vaccinate.

Note: in the real world, people aren't caught in this bind. We don't know there's herd immunity against any particular disease. We can always justifiably think vaccinating a child has some chance of benefitting both the child and others. (And by the way, my own children did receive all the routine vaccinations plus others.)

The scenario isn't real, but it also isn't far-fetched. People could be sure their community has herd immunity against X, and it seems to me these two arguments would genuinely compete for our attention in such a situation. Though I initially lean toward argument #1, it does strike me as strange for a parent to have a child jabbed, in the full knowledge that this is "for fairness" and without benefit to the child or anyone else. Thus: puzzlement.

5/13/14

Freeriding and the PTA

For purposes of writing a book chapter about vaccination ethics, I've been thinking about freeriding. Never mind vaccination for the moment. Let's talk about flowers.

A long time ago the PTA at my kids' elementary school did a lovely job of planting bushes and flowers in front of the school. We paid our PTA dues, but that's it. By the usual definition of "freerider" I seem to be one--I received the benefit of the planting, but didn't fully pay for it, since I did none of the labor. My reasons for not helping seem to acquit me, though, which goes to show that "freerider" isn't automatically pejorative. A "freerider" is not necessarily a freeloader, a moocher, a cheat. There are innocent freeriders and guilty freeriders.

So, my reasons. I benefited from the flowers, but really just by accident. I couldn't help but pass by them when taking my kids to school. I can't say that I wanted to see them planted, beyond a casual "that's nice." I wasn't doing so little to help because others were doing so much. Had they done less, so there would have been no flowers, I would have done just as little. To be a bad freerider, I have to (a) benefit from a public good without fully paying but I also have to (b) endorse the good--care about it, want it, as opposed to merely receiving it. There are some things we all must be presumed to care about -- clean air, good health, etc. -- but flowers aren't among those things. I can't be accused of self-deception if I say I didn't care (much) about the flowers.

Suppose I had really cared about the flowers but lots of people wanted to plant them. In that case, my contribution would have been gratuitious or worse. I would have been in the way, or might have crowded out another eager worker. To be a bad freerider, I'd have to meet conditions (a) and (b) but also something like (c): I could contribute without excluding those for whom helping is a privilege (assuming for me it's not).

Then we need a condition having to do with self-harm. A bad freerider meets conditions (a), (b), (c) and also (d): I could contribute without causing excessive harm to myself or others. Of course, I might have a slightly aching back afterwards, and my child might be slightly less happy during my absence. But I'm excused if helping is going to mean having a heart attack or abandoning my sick child, or what have you.

Again, never mind vaccination. I'm pondering, for the moment, whether this is a good enough definition of "bad freerider" for purposes of deciding when you have to participate in PTA activities and when you don't.

A long time ago the PTA at my kids' elementary school did a lovely job of planting bushes and flowers in front of the school. We paid our PTA dues, but that's it. By the usual definition of "freerider" I seem to be one--I received the benefit of the planting, but didn't fully pay for it, since I did none of the labor. My reasons for not helping seem to acquit me, though, which goes to show that "freerider" isn't automatically pejorative. A "freerider" is not necessarily a freeloader, a moocher, a cheat. There are innocent freeriders and guilty freeriders.

So, my reasons. I benefited from the flowers, but really just by accident. I couldn't help but pass by them when taking my kids to school. I can't say that I wanted to see them planted, beyond a casual "that's nice." I wasn't doing so little to help because others were doing so much. Had they done less, so there would have been no flowers, I would have done just as little. To be a bad freerider, I have to (a) benefit from a public good without fully paying but I also have to (b) endorse the good--care about it, want it, as opposed to merely receiving it. There are some things we all must be presumed to care about -- clean air, good health, etc. -- but flowers aren't among those things. I can't be accused of self-deception if I say I didn't care (much) about the flowers.

Suppose I had really cared about the flowers but lots of people wanted to plant them. In that case, my contribution would have been gratuitious or worse. I would have been in the way, or might have crowded out another eager worker. To be a bad freerider, I'd have to meet conditions (a) and (b) but also something like (c): I could contribute without excluding those for whom helping is a privilege (assuming for me it's not).

Then we need a condition having to do with self-harm. A bad freerider meets conditions (a), (b), (c) and also (d): I could contribute without causing excessive harm to myself or others. Of course, I might have a slightly aching back afterwards, and my child might be slightly less happy during my absence. But I'm excused if helping is going to mean having a heart attack or abandoning my sick child, or what have you.

Again, never mind vaccination. I'm pondering, for the moment, whether this is a good enough definition of "bad freerider" for purposes of deciding when you have to participate in PTA activities and when you don't.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)