Reading around in the philosophical literature about self and identity, it strikes me that one topic is very often left out. The literature deals with quantitative identity, as in the relation between teenage me and adult me that makes "us" one and the same. There's plenty of literature about the self--in the sense of my mind, in totality. There's also literature about the self in the sense of personality--clusters of traits like introversion, openness to new things, etc.. But what about identity in the sense of a relatively small set of core characteristics that go into "who I am" (as the folk are wont to say)?

This is the sense of "identity" relevant to the subtitle of Andrew Solomon's book Far from the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity. What are we searching for? Knowing who we are -- in some sense. The idea seems to be that healthy, normal people can give an answer to the question "Who am I?" Beyond just having whole personalities, which is inevitable, it's thought to be important and wholesome to be able to say "This is who I am--I'm X, Y, and Z." Solomon says the people discussed in his book have "horizontal" identities. Being Irish, because your parents are Irish, would be a vertical identity. Being deaf or autistic (for example) is having a horizontal identity, because you don't derive that identity from your parents.

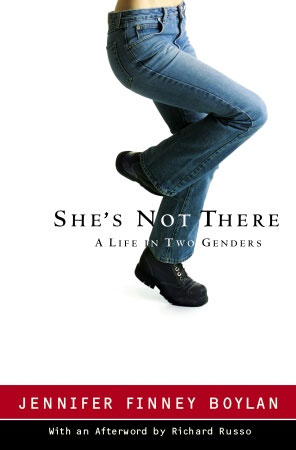

What are my X, Y, and Z? Let's see--maybe this is a reasonable test. You have a randomly selected pen pal or e-pal, and know nothing about each other. What information do you need to share so that you know who you're talking to? The folk theory about identity is that for each person, there is an answer to that question. Our identities are built up out of things like our gender, occupation, or even where we live. (Some Texans are identity-Texans!) Inspired by the chapter of Solomon's book on transgender, I've been reading around about that topic (I very much enjoyed She's Not There, by Jennifer Finney Boylan). Gender, to me, seems like part of the background. I'm female, but don't think much about being female. I wouldn't really have thought it was part of my identity, but maybe it is--it's just a part of my identity that I don't focus on much. Does my invisible interlocutor need to know my gender, so we know each other? Maybe so. I'm a vegetarian, but not an identity-vegetarian. My interlocutor doesn't need to know that about me, to know who I am. Being Jewish--maybe. Being an atheist--maybe not. Being a mother of two children--probably. Being a philosopher--very probably.

A Buddhist-Stoic element of the folk theory about identity is that we shouldn't put too many features on such a list, since doing so would make us vulnerable to the proverbial "identity crisis"--if I lose my job, and that's part of my identity, I shall have to run into the night screaming, because I no longer can say who I am. We need to put the right kinds of things on the list--not my job, but my love of the subject I teach, for example. Some disability activists offer another type of advice--we actually shouldn't think of a disability or difference as identity-making, contrary to Solomon's subtitle. Why regard yourself or someone else as a deeply different kind of person, solely on the basis of a disability? Turning disabilities into identities is at the root of some kinds of segregation and discrimination.

Being more tough-minded about all this, you have to wonder: why should any of my characteristics define who I am? Maybe--in fact, probably-- there's no definition of who I am, in this sense, no traits, attitudes, beliefs, and so on, that make me who I am. Maybe "identity" and "who I am" talk is folk psychology at its least salvageable. At the risk of using the word "maybe" too many times in one post, I have to say: maybe.

I think that there is something really strange about trying to boil down an identity to a few traits or qualities, when it is so obvious that so many of our traits are fairly dynamic, in a way that is beyond our control, typically.

ReplyDeleteDid I really choose to be a professor? Sure, but my choice wasn't the only thing that made me being a professor possible, job openings, my hiring committee, who could have just have been another random set of people who wouldn't have liked me, etc.

For example, I loved Breaking Bad, but is that part of my identity? Is it really going to be any part of me in 10 years? I love philosophy, but will I in 10 years, or will I have some kind of epiphany and turn my back on the subject? Surely not out of the question. Maybe my wife will get sick of me, divorce me, and I find a new place to live that doesn't allow me to be a philosophy professor, so I end up gardening for a living, which I fall madly in love with.

The very problem of identity, how do we maintain an continuous identity, in spite of the change that we undergo, really I think rules out these kinds of attempts to fix our identity, be it metaphysical or in the "who am I" sense.