Rats with a spinal cord injury that left their hind legs completely paralyzed learned to walk again on their own after an intensive training course that included electrical stimulation of the brain and the spine, scientists reported on Thursday.Obviously the rats don't just have this injury, they're injured by the experimenters. An awful thought, but it's easy to substitute an image of a paraplegic walking again for the rat ... and then this seems like a major victory.

Pages

▼

5/31/12

Rat Walks Again

This picture and story captures what's so heart-wrenching about the whole subject of animal experimentation.

5/30/12

Conference Behavior

I think this is funny. So you

give a speech at a conference, and afterwards a couple comes up to you and

hands you a business card, saying (essentially) "care to join

us?" For details and the card see

here. Question: when

should moronic behavior be treated as private vice, to be discouraged

informally; and when should moronic behavior be proscribed by the quasi-legal

standards of a community (official conference policy, in this case); and when

should moronic behavior be flat out illegal? Hmm. This would

be a fun case for someone who teaches sexual ethics (alas, I don't).

5/29/12

My Sweet Lord

Song for the day is "My Sweet Lord" -- we've been having a George Harrison fest, as a result of watching the new(ish) Martin Scorsese movie about his life (which is very good). There's something utterly ingenious about religious thinking. I've noticed, as I age, that I'm getting more and more creaky, and it really, really sucks. Being a believer let's you think, as you fall apart, that you're getting closer and closer to meeting your lord. "Really want to see you, really want to know you ..." I often think it would be great to believe such things. If I ever get offered a spot in an "experience machine" I'd like to program in being a believer listening to "My Sweet Lord." It must be pretty cool. Anyhow, the song (which is sooooo good, even without belief) --

5/28/12

Attachment Parenting

I guess I have to read Elisabeth Badinter's book The Conflict: How Modern Motherhood Undermines the Status of Women, but I think it's going to be supremely irritating, judging by this review and Katha Pollitt's column, both in The Nation. The bad guy du jour is "attachment parenting," which says good mothers/parents need to be in super-contact with their children, wearing them in slings, breastfeeding them as long as possible, sleeping with them in a "family bed"--none of which is compatible with maintaining a full-time job. This kind of motherhood "undermines the status of women" so ... baaaaaad.

Except it's really much more complicated. This paragraph from Pollitt's column gets things all wrong--

You have a kid (or two, in my case). Your every instinct is not to let the vulnerable little people out of your sight. You love the closeness of breastfeeding. You sometimes bring crying babies into bed in the middle of the night--it just feels right. The idea of leaving them in the care of someone else all day is distressing. You do everything else in your life "full-tilt" and want to parent that way too.

Yet lots of advice books tell you that your impulses are wrong. There's the feminist idea that you must return to full-time work right away. Work is always respectable, no matter what it consists of -- just because you're paid, I suppose. There are lots of books that promote an authoritarian style of parenting that says you shouldn't respond to your baby at night. There's the onslaught of media images that say breasts are for sex, not for feeding baby. Then you discover "attachment parenting"--and suddenly what you wanted to do anyway becomes OK. You learn that it's not unheard of for women to want to stay close with their kids--there are lots of cultures in which this is standard fare. William Sears's books are a bit over the top, and I wouldn't dream of following his advice to a T (or anyone else's, for that matter), but the message in them is welcome--for many women it's the message that their own intuitions are OK. Far from increasing guilt, the books alleviate guilt--in the woman whose instincts mesh with that parenting-style.

So I don't buy this idea that attachment-style parenting is inflicted on women, and can just be discarded, to overcome the work-family conflict that's a problem for many women. Attachment-style parenting (at least in its essentials) runs deep, and many women choose it for themselves. Those that don't care for it have dozens, if not hundreds, of other child-care books to choose from. There's plenty of validation out there for people who want to parent in a different style, or who want to return to work and personal freedom as quickly as possible.

The question to my mind is how women can spend part of their lives in a family focused way, and yet fully "recover" (so to speak)--returning to careers, preserving financial viability, and so on. It would help if there were on-site daycare, so you can both work and be close to baby--for someone people, that would be enough. It would help if there were part-time opportunities for both men and women. Some people hate the idea of a stranger taking care of their child all day, but are happy with the thought of another parent being in charge. But for those who really want to spend 5 or 10 years with parenting as their primary focus, why must that be the death of career and financial stability? In any event, it just won't do to pretend that super-attached parenting is a nefarious plot, and not just what some women genuinely want.

Except it's really much more complicated. This paragraph from Pollitt's column gets things all wrong--

I was originally going to write this column as an attack on women who have fallen for the attachment-parenting spiel, which makes them feel endlessly guilty and then encourages them to project that guilt outward onto more relaxed mothers. Women are so eager to blame themselves and one another about, well, everything—weight, looks, clothes, sexual behavior (you haven’t lived till you’ve heard a seventh-grade girl refer to another as a “ho”), marriages and, of course, baybeez, every wrinkle of whose behavior is directly attributable to their mothers’ having made some small but fatal mistake.Despite the disclaimer, this is an attack on mothers who attachment-parent. Has Pollitt ever met any? I have, because I sort of liked that kind of thing when my kids were young and so did many of my friends. Pollitt imagines women go into parenthood with no thoughts and feelings of their own and then get suckered into attachment-parenting--there's the spiel, and then the guilt, and then the work-family conflict, and then the attached mom starts laying guilt on other mothers. But no, the sequence of events is rather this--

You have a kid (or two, in my case). Your every instinct is not to let the vulnerable little people out of your sight. You love the closeness of breastfeeding. You sometimes bring crying babies into bed in the middle of the night--it just feels right. The idea of leaving them in the care of someone else all day is distressing. You do everything else in your life "full-tilt" and want to parent that way too.

Yet lots of advice books tell you that your impulses are wrong. There's the feminist idea that you must return to full-time work right away. Work is always respectable, no matter what it consists of -- just because you're paid, I suppose. There are lots of books that promote an authoritarian style of parenting that says you shouldn't respond to your baby at night. There's the onslaught of media images that say breasts are for sex, not for feeding baby. Then you discover "attachment parenting"--and suddenly what you wanted to do anyway becomes OK. You learn that it's not unheard of for women to want to stay close with their kids--there are lots of cultures in which this is standard fare. William Sears's books are a bit over the top, and I wouldn't dream of following his advice to a T (or anyone else's, for that matter), but the message in them is welcome--for many women it's the message that their own intuitions are OK. Far from increasing guilt, the books alleviate guilt--in the woman whose instincts mesh with that parenting-style.

So I don't buy this idea that attachment-style parenting is inflicted on women, and can just be discarded, to overcome the work-family conflict that's a problem for many women. Attachment-style parenting (at least in its essentials) runs deep, and many women choose it for themselves. Those that don't care for it have dozens, if not hundreds, of other child-care books to choose from. There's plenty of validation out there for people who want to parent in a different style, or who want to return to work and personal freedom as quickly as possible.

The question to my mind is how women can spend part of their lives in a family focused way, and yet fully "recover" (so to speak)--returning to careers, preserving financial viability, and so on. It would help if there were on-site daycare, so you can both work and be close to baby--for someone people, that would be enough. It would help if there were part-time opportunities for both men and women. Some people hate the idea of a stranger taking care of their child all day, but are happy with the thought of another parent being in charge. But for those who really want to spend 5 or 10 years with parenting as their primary focus, why must that be the death of career and financial stability? In any event, it just won't do to pretend that super-attached parenting is a nefarious plot, and not just what some women genuinely want.

5/24/12

Coyne on Evolution and Religion

Jerry Coyne has a new article out on how religiosity gets in the way of Americans accepting evolution. I'm surprised he continues a pattern of reasoning that was widely criticized over a year ago. First he dismisses religious scientists as "proof" of religion-science compatibility--

Why worry about "proof" in the first passage, and then lower the bar, making the issue "evidence" in the second passage? With evidence the topic in both passages, both the religious scientists and the formerly religious scientists come out to be some evidence. But it doesn't seem as if Coyne wants to accept the religious scientists as any evidence at all, since he dismisses them entirely with the Whitman quote and the Christian adultery point.

Now, if you've made up your mind that religion and science are logically incompatible (cannot both be all true) on some independent basis, then yes, you can dismiss Francis Collins as compartmentalizing (that's what you've got to think--or something along those lines), and you can think formerly religious scientists are reasoning when science gradually crowds out religion for them. But in that case, you've got some other basis for thinking religion and science are incompatible. What's really hard to do, if you're being fair and logical, is both dismiss religious scientists as any evidence at all for science-religion compatibility and also use formerly religious scientists as some evidence for science-religion incompatibility.

Now maybe, maybe, there could be special reasons for the different treatment. Maybe you've got evidence of compartmentalizing in the religious scientists. They may actually utter the words of Whitman's poem themselves! Maybe you've got evidence of reasoning in the formerly religious scientists--you've caught them going from premises about science to negative conclusions about religion. But barring special evidence of that sort, if you think scientists losing religion count as some evidence for incompatibility, you have to think scientists not losing religion count as some evidence for compatibility. Right? Right!

Of course religious scientists aren't proof of compatibility, but you might think they're some evidence. In fact, you would almost have to think so, if, like Coyne, you regarded it as evidence of incompatibility that people lose religion as they develop into elite scientists--Some argue that the mere existence of religious scientists proves this compatibility, but that is specious. That people can simultaneously hold two conflicting worldviews in their head is evidence not for compatibility but for Walt Whitman’s (1855) solipsistic admission, “Do I contradict myself?/ Very well, then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.).” This argument for science/faith compatibility is like saying that Christianity and adultery are compatible because many Christians are adulterers.

Further evidence for incompatibility comes from the huge disparity in religiosity between scientists and laypeople. While only 6% of the American public describe themselves as atheists or agnostics, 64% of scientists at “elite” American universities fall into these classes (Ecklund 2010; similar results were found by Larson and Witham 1997). This figure is much higher for more accomplished scientists. A survey by Larson and Witham (1998) showed that that 93% of members of the National Academy of Sciences, America’s most elite body of scientists, are agnostics or atheists, with just 7% believing in a personal God. This is almost the exact reverse of figures for the American public as a whole.

This disparity bespeaks a profound disconnect between faith and science. Regardless of whether it reflects the attraction of nonbelievers to science, or the fact that science erodes religious belief—both are undoubtedly true—the incompatibility remains.

Why worry about "proof" in the first passage, and then lower the bar, making the issue "evidence" in the second passage? With evidence the topic in both passages, both the religious scientists and the formerly religious scientists come out to be some evidence. But it doesn't seem as if Coyne wants to accept the religious scientists as any evidence at all, since he dismisses them entirely with the Whitman quote and the Christian adultery point.

Now, if you've made up your mind that religion and science are logically incompatible (cannot both be all true) on some independent basis, then yes, you can dismiss Francis Collins as compartmentalizing (that's what you've got to think--or something along those lines), and you can think formerly religious scientists are reasoning when science gradually crowds out religion for them. But in that case, you've got some other basis for thinking religion and science are incompatible. What's really hard to do, if you're being fair and logical, is both dismiss religious scientists as any evidence at all for science-religion compatibility and also use formerly religious scientists as some evidence for science-religion incompatibility.

Now maybe, maybe, there could be special reasons for the different treatment. Maybe you've got evidence of compartmentalizing in the religious scientists. They may actually utter the words of Whitman's poem themselves! Maybe you've got evidence of reasoning in the formerly religious scientists--you've caught them going from premises about science to negative conclusions about religion. But barring special evidence of that sort, if you think scientists losing religion count as some evidence for incompatibility, you have to think scientists not losing religion count as some evidence for compatibility. Right? Right!

5/23/12

The Second Sexism (plus a mystery or two)

I have my eye on the book The Second Sexism -- to read it, or not to read it? We will certainly review it at The Philosophers' Magazine and Benatar is writing an essay on discrimination against men for the magazine. If nothing else, the book is intriguing, and it sure has a clever title. But ...

Honestly, I cannot say that I feel the problem of sexism against men looms large, especially compared with the problem of sexism against women. I laughed when I read a column at the Guardian that accuses Benatar of "victim-envy". Next thing we'll be finding out that rich people are terribly mistreated too. And don't forget to pity the poor gorgeous people! On the other hand, in The New Stateman Ally Fogg says Benatar gives full credit to feminism and just wants proper attention paid to anti-male discrimination as well. So I will do my best to withhold judgment until I've read the book or learned more about it from a reliable reviewer. (Full disclosure: my own book Animalkind is in the same series as Benatar's.)

OK, now for the mysteries. One is about the connection between The Second Sexism and Benatar's last book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Women have traditionally played the larger role in creating and raising children and Benatar thinks we harm people by bringing them into the world. Does that anti-natal stance make him less sympathetic to women? Just asking. (I was gratified to learn that I'm not the only one "just asking"--Christine Overall asks similar questions in her recent book Why Have Children?)

The other mystery...

First let me refer you to an interesting blog post by James Garvey on whether it's legitimate to be interested in the personal lives of philosophers. I say "of course". Being interested in people's lives is the engine behind literature and movies, and I make no apologies for my curiosity. Now, whether people's lives shed any light on the believability of their philosophical views is another matter. I'd even say "quite possibly" to that. But let's keep the focus just on lives, period. I like to know what people look like, at the very least, but in the case of someone with views as extraordinary as Benatar's, I'll go a little further. It would be fun to know some personal details. Does the author of Better Never to Have Been has 10 children? Does the author of The Second Sexism have three angry ex-wives? Probably not, but it would be fun to know.

No, I refuse to be ashamed of myself for wondering. (Perhaps Emrys Westacott's book The Virtues of Our Vices could help me defend myself. I believe he's got a defense of gossip in there.)

OK, so here's mystery #2. I was curious to know what Benatar looks like, but that's been hard to find out. Yesterday I thought I'd hit the jackpot, because I found a YouTube video of a debate he participated in (about admissions at the University of Cape Town--he argues against race-based affirmative action). However the videographer trains his/her camera on the other five panelists, but deliberately keeps Benatar out of view (he's the speaker furthest to the right). The minute it's his turn to talk, we see him for a spit second (at 8:54), and then the camera focuses on the audience and avoids him (see 10:19 and 12:55). What's up here?

Sherlock, take it away!

Honestly, I cannot say that I feel the problem of sexism against men looms large, especially compared with the problem of sexism against women. I laughed when I read a column at the Guardian that accuses Benatar of "victim-envy". Next thing we'll be finding out that rich people are terribly mistreated too. And don't forget to pity the poor gorgeous people! On the other hand, in The New Stateman Ally Fogg says Benatar gives full credit to feminism and just wants proper attention paid to anti-male discrimination as well. So I will do my best to withhold judgment until I've read the book or learned more about it from a reliable reviewer. (Full disclosure: my own book Animalkind is in the same series as Benatar's.)

OK, now for the mysteries. One is about the connection between The Second Sexism and Benatar's last book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Women have traditionally played the larger role in creating and raising children and Benatar thinks we harm people by bringing them into the world. Does that anti-natal stance make him less sympathetic to women? Just asking. (I was gratified to learn that I'm not the only one "just asking"--Christine Overall asks similar questions in her recent book Why Have Children?)

The other mystery...

First let me refer you to an interesting blog post by James Garvey on whether it's legitimate to be interested in the personal lives of philosophers. I say "of course". Being interested in people's lives is the engine behind literature and movies, and I make no apologies for my curiosity. Now, whether people's lives shed any light on the believability of their philosophical views is another matter. I'd even say "quite possibly" to that. But let's keep the focus just on lives, period. I like to know what people look like, at the very least, but in the case of someone with views as extraordinary as Benatar's, I'll go a little further. It would be fun to know some personal details. Does the author of Better Never to Have Been has 10 children? Does the author of The Second Sexism have three angry ex-wives? Probably not, but it would be fun to know.

No, I refuse to be ashamed of myself for wondering. (Perhaps Emrys Westacott's book The Virtues of Our Vices could help me defend myself. I believe he's got a defense of gossip in there.)

OK, so here's mystery #2. I was curious to know what Benatar looks like, but that's been hard to find out. Yesterday I thought I'd hit the jackpot, because I found a YouTube video of a debate he participated in (about admissions at the University of Cape Town--he argues against race-based affirmative action). However the videographer trains his/her camera on the other five panelists, but deliberately keeps Benatar out of view (he's the speaker furthest to the right). The minute it's his turn to talk, we see him for a spit second (at 8:54), and then the camera focuses on the audience and avoids him (see 10:19 and 12:55). What's up here?

Sherlock, take it away!

5/18/12

The Republican Brain

Something about the title of this book elicits skepticism. I wouldn't read a book called The Liberal Brain, if it were written by a conservative (did Ann Coulter actually write a book with that title)? Why expect objectivity from a liberal trying to dissect the Republican brain? Actually, if you read the book, you do get an answer. Liberals, more than Conservatives, love to be fair and nuanced. They value empathy highly, so will work hard to see things from the other side's vantage point. Mooney works pretty hard on that, and doesn't whitewash liberals.

Here's the kind of thing I want to understand. Do any Republicans really think Obama is a Muslim, or do they just pretend to think so for effect? What's running through the minds of people who doubt climate change is real and human-caused, despite the views of the vast majority of climate scientists? Do abortion foes really think abortion causes breast cancer, even though there's no good evidence of that? These are really extraordinary phenomena. It would take a lot for me to say "now I understand".

Mooney reports findings that Republicans do more "motivated reasoning" than Democrats. Their response to evidence is more colored by their preconceptions. There are also considerable differences in personality, with relevance to political outlook. Democrats score higher on openness, Republicans on conscientiousness. For lots of reasons (their greater openness is a factor), Democrats are more attracted to science and Republicans more wary of science. Etc. (This isn't meant to be an exhaustive summary.)

I don't quite have a "now I get it" reaction from the book. To get that I might need to get more deeply into the vantage point of Republicans (see, liberals like me do value empathy highly!). One thing that might be going on is that conservatives think they're paddling upstream. The current is running in a liberal direction. We are quickly getting more freedom, a breakdown of categories (two brides in one wedding -- OMG), lots of sexual license, more government. Paddling upstream makes you desperate and frantic.

Then again, when liberals feel like they're paddling upstream, and therefore get desperate, they don't show the same degree of contempt for science. Take far left greens, who think we need to combat genetic engineering, and nuclear power. Or far left liberals of the 1970s, who were so upset about sociobiology. Or far left feminists today, some of whom absolutely won't acknowledge any innate sex differences. On the left, motivated reasoners will pick sides in a scientific dispute based on an ideology, but will only rarely turn their backs on all of science. On the left, we're basically science fans. Why is that not the case on the right?

The personality explanation only seems to take you so far. It's just not clear the differences are huge enough to explain the extreme indifference to science that we see on the right. Perhaps you ultimately have to say more about religion. David Frum says this (p. 143): "...if you are an intensely committed Christian and especially an evangelical Christian, you do feel yourself kind of beleaguered in an intellectual world that's not hospitable to you, and that feeling of isolation and victimization is then spread through the tone and style of the whole conservative world."

One might hypothesize that conservative Christians have lots of practice being indifferent to science, because of their religious stance, and that's the main reason they're capable of turning their backs on so much science when it comes to climate change, abortion, Obama's background, etc. Mooney points mainly to more general features of the personalities and cognitive styles of Republicans. Thus, the book is in synch with another (off stage, mostly) part of Mooney's outlook--his wish to avoid being a religion-basher.

Anyhow--interesting book, worth reading.

Here's the kind of thing I want to understand. Do any Republicans really think Obama is a Muslim, or do they just pretend to think so for effect? What's running through the minds of people who doubt climate change is real and human-caused, despite the views of the vast majority of climate scientists? Do abortion foes really think abortion causes breast cancer, even though there's no good evidence of that? These are really extraordinary phenomena. It would take a lot for me to say "now I understand".

Mooney reports findings that Republicans do more "motivated reasoning" than Democrats. Their response to evidence is more colored by their preconceptions. There are also considerable differences in personality, with relevance to political outlook. Democrats score higher on openness, Republicans on conscientiousness. For lots of reasons (their greater openness is a factor), Democrats are more attracted to science and Republicans more wary of science. Etc. (This isn't meant to be an exhaustive summary.)

I don't quite have a "now I get it" reaction from the book. To get that I might need to get more deeply into the vantage point of Republicans (see, liberals like me do value empathy highly!). One thing that might be going on is that conservatives think they're paddling upstream. The current is running in a liberal direction. We are quickly getting more freedom, a breakdown of categories (two brides in one wedding -- OMG), lots of sexual license, more government. Paddling upstream makes you desperate and frantic.

Then again, when liberals feel like they're paddling upstream, and therefore get desperate, they don't show the same degree of contempt for science. Take far left greens, who think we need to combat genetic engineering, and nuclear power. Or far left liberals of the 1970s, who were so upset about sociobiology. Or far left feminists today, some of whom absolutely won't acknowledge any innate sex differences. On the left, motivated reasoners will pick sides in a scientific dispute based on an ideology, but will only rarely turn their backs on all of science. On the left, we're basically science fans. Why is that not the case on the right?

The personality explanation only seems to take you so far. It's just not clear the differences are huge enough to explain the extreme indifference to science that we see on the right. Perhaps you ultimately have to say more about religion. David Frum says this (p. 143): "...if you are an intensely committed Christian and especially an evangelical Christian, you do feel yourself kind of beleaguered in an intellectual world that's not hospitable to you, and that feeling of isolation and victimization is then spread through the tone and style of the whole conservative world."

One might hypothesize that conservative Christians have lots of practice being indifferent to science, because of their religious stance, and that's the main reason they're capable of turning their backs on so much science when it comes to climate change, abortion, Obama's background, etc. Mooney points mainly to more general features of the personalities and cognitive styles of Republicans. Thus, the book is in synch with another (off stage, mostly) part of Mooney's outlook--his wish to avoid being a religion-basher.

Anyhow--interesting book, worth reading.

5/15/12

#1,000

|

| Erick Swenson, Untitled 2000, The Modern, Fort Worth |

Instead, let's have some footnotes. I've been working on my TPM column, which is going to be about the artist Erick Swenson, and the disgusting (but cool) stuff he has on exhibit at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. (The dog with cape above is at The Modern in Fort Worth, and isn't part of his disgusting oeuvre.) The interesting thing (to me) is the way the Nasher exhibit connects with Colin McGinn's book The Meaning of Disgust. The book sheds some light on what Swenson is up to, but the exhibit ultimately falsifies the theory in the book. (You'll just have to read the column when it comes out.)

Anyway, for footnotes we have

1. This fun article about where Swenson lives. Terrific! You even get to see what his bedroom looks like. I wonder about people, and especially wonder about the likes of Swenson. What must it be like for his girlfriend to see him hunched over a dead deer sculpture for 5 years? Sounds like she files it all under "Life with an Artist."

2. In the column I talk briefly about the toxicity theory of morning sickness which an author by the name of Margie Profet was putting forward in the 90s. So I got to thinking "Whatever happened to Margie Profet?" Well this is interesting!

3. The review of McGinn that I discuss--well, you just have to read it. Nina Strohminger is very funny, but I think she underestimates McGinn's own sense of humor. I don't think The Meaning of Disgust is unintentionally funny, or at least the funniness of the book is not completely unintentional.

4. Yes, McGinn is worth reading too, as much as his theory is unbelievable. There are nevertheless some memorable insights in there. "Shit, shockingly, is the sine qua non of the soul." Well, it's true! And other good stuff.

5. More Swenson images. I really like his artwork.

* Including unpublished drafts and other detritus --

Religion for Atheists

When Alain De Botton gets done building his temple for atheists, I'd like to be appointed the music director. Let's definitely have a lot of Bjork. Why? Because her music creates the sort of experience religious people get to have, and De Botton thinks the godless should have as well. Or perhaps more like it -- a successor experience. Something grand, emotional, and full of wonder, but without the worshipful part. I'm just a bit obseessed with Bjork! This is from the album Homogenic --

5/10/12

What a Philosopher Looks Like

I'm really enjoying these pictures. They show that philosophers don't all look the same and don't spend all their time with their heads buried in books. That's great, but hey--there is a look. Philosophers look a bit more natural, disheveled, and unconventional than most people. The men are less clean-cut, the women are less coiffed and artificial. There are more men than women, and white folk predominate. Just sayin'. I'm tempted to submit a picture, but I've got nothing too terrific--no fantastic pictures of my ass, no pictures of me dancing or with a bird on my head, no shots of me operating heavy machinery. In short, nothing that really challenges preconceptions about what a philosopher looks like. Sigh. I am a pretty typical looking philosopher, apart from being female.

Elsewhere in the news, and for no particular reason: I'm excited about reading The Republican Brain, by Chris Mooney. My son got it for me for my birthday (yesterday--yes, I am now older--this is so exciting!).

Elsewhere in the news, and for no particular reason: I'm excited about reading The Republican Brain, by Chris Mooney. My son got it for me for my birthday (yesterday--yes, I am now older--this is so exciting!).

5/9/12

5/8/12

Maurice Sendak Talks to Stephen Colbert

| The Colbert Report | Mon - Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Grim Colberty Tales with Maurice Sendak Pt. 1 | ||||

| www.colbertnation.com | ||||

| ||||

| The Colbert Report | Mon - Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| Grim Colberty Tales with Maurice Sendak Pt. 2 | ||||

| www.colbertnation.com | ||||

| ||||

5/7/12

Everyone's Talking About ...

Markets. Scott Carney's book The Red Market is one of the most interesting things I read (and blogged about) last year. It's about the international market in hair, blood, kidneys, eggs, sperm, wombs ... and children. Carney confines himself mostly to reporting the facts about these strange markets, but you get a strong sense that he thinks there's something fundamentally wrong with them all. This makes a terrific philosophy puzzle. Find the problem with these kinds of markets. What exactly is it?

Some will say it's problematic when you have an intuition first, and then look for a way to justify it. Jonathan Haidt says (see "The Emotional Dog and it's Rational Tail" here) you're bound to be just confabulating--making up some rationale for attitudes you're going to stick with come what may. Fair enough, if you really are dead-set on validating your intuitions, no matter what further reflection and fact-gathering turns up. I would not say I'm not dead-set. In fact, my views on some of those markets have changed somewhat over time.

Anyhow, after reading The Red Market you really need books to help you think about the ethics of these markets, and I'm amazed by how many have come out recently. Right now I'm reading Debra Satz's book What Some things Should Not be for Sale: The Moral Limits of Markets. Next on my list will be Michael Sandel's new book What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. Then, if any appetite for the topic remains, I might look at Arlie Hochschild's new book The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times. After that (phew!), maybe Free Market Fairness, by John Tomasi.

Next question: why so many books about strange markets? That's curious ....

Some will say it's problematic when you have an intuition first, and then look for a way to justify it. Jonathan Haidt says (see "The Emotional Dog and it's Rational Tail" here) you're bound to be just confabulating--making up some rationale for attitudes you're going to stick with come what may. Fair enough, if you really are dead-set on validating your intuitions, no matter what further reflection and fact-gathering turns up. I would not say I'm not dead-set. In fact, my views on some of those markets have changed somewhat over time.

Anyhow, after reading The Red Market you really need books to help you think about the ethics of these markets, and I'm amazed by how many have come out recently. Right now I'm reading Debra Satz's book What Some things Should Not be for Sale: The Moral Limits of Markets. Next on my list will be Michael Sandel's new book What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. Then, if any appetite for the topic remains, I might look at Arlie Hochschild's new book The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times. After that (phew!), maybe Free Market Fairness, by John Tomasi.

Next question: why so many books about strange markets? That's curious ....

5/5/12

Ethics minus religion = thin gruel?

Didn't see this until now -- "Room for Debate" at the New York Times, with Rhys Southan weighing in interestingly (as usual).

Elsewhere in vegan-world, Gary Francione has an interesting, long essay about moral realism and "new atheism". It bothers him, as it does me, that new atheists often accept the following equation: ETHICS minus RELIGION = THIN GRUEL. In academic ethics, that equation is usually rejected. Generally, new atheists think giving up God makes a much bigger difference to everything than it really does. A prime example of the "huge difference" view (perhaps we should talk about "huge difference atheism" rather than "new atheism") is Alex Rosenberg's book The Atheist's Guide to Reality: Enjoying Life without Illusions, which I'm reviewing in an upcoming issue of Free Inquiry. This is HD Atheism cubed. My 2,000 word review, reduced to one word, would be "no". More on that when the review comes out.

Elsewhere in vegan-world, Gary Francione has an interesting, long essay about moral realism and "new atheism". It bothers him, as it does me, that new atheists often accept the following equation: ETHICS minus RELIGION = THIN GRUEL. In academic ethics, that equation is usually rejected. Generally, new atheists think giving up God makes a much bigger difference to everything than it really does. A prime example of the "huge difference" view (perhaps we should talk about "huge difference atheism" rather than "new atheism") is Alex Rosenberg's book The Atheist's Guide to Reality: Enjoying Life without Illusions, which I'm reviewing in an upcoming issue of Free Inquiry. This is HD Atheism cubed. My 2,000 word review, reduced to one word, would be "no". More on that when the review comes out.

5/4/12

NYT Meat Contest Winner

It's Jay Bost, here and below.

**

I can't say that I'm impressed, despite the thoughtfulness and nice writing. There's even a factual error in the essay:

In fact, the general trend is toward even more animal farming being foolish and wrong. Populations are growing, affluence is increasing, affluent people are eating more meat, and we're running out of land. For all those reasons, the overall trend is toward an even bigger "most" being foolish and wrong.

It's one thing to eat meat you bought at Whole Foods--OK, it's better than McDonald's. It's another thing to think there's something exemplary and visionary about this, like you're leading the way to a better future. I don't think that can possibly be true, given diminishing available land.

For my money, the "manure" essays were better. They raised a very fundamental question about how plant and animal farming may be intertwined. If this is so, then you're complicit in killing animals whether you eat them or not. I think that's an interesting possibility.

Actually, I like my own effort on this topic. In a meat-free world, a staggering amount of the planet would be unavailable for food collection and production. I find that "food" for thought.

As a vegetarian who returned to meat-eating, I find the question “Is

meat-eating ethical?” one that is in my head and heart constantly. The

reasons I became a vegetarian, then a vegan and then again a

conscientious meat-eater were all ethical. The ethical reasons of why

NOT to eat meat are obvious: animals are raised and killed in cruel

conditions; grain that could feed hungry people is fed to animals; the

need for pasture fuels deforestation; and by eating meat, one is

implicated in the killing of a sentient being. Except for the last

reason, however, none of these aspects of eating meat are implicit in

eating meat, yet they are exactly what make eating some meat unethical.

Which leads to my main argument: eating meat raised in specific

circumstances is ethical; eating meat raised in other circumstances is

unethical. Just as eating vegetables, tofu or grain raised in certain

circumstances is ethical and those produced in other ways is unethical.

What are these “right” and “wrong” ways of producing both meat and plant

foods? For me, they are most succinctly summed up in Aldo Leopold’s

land ethic: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity,

stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends

otherwise.” While studying agroecology at Prescott College in Arizona, I

was convinced that if what you are trying to achieve with an “ethical”

diet is the least destructive impact on life as a whole on this planet,

then in some circumstances, like living among dry, scrubby grasslands in

Arizona, eating meat, is, in fact, the most ethical thing you can do

other than subsist on wild game, tepary beans and pinyon nuts. A

well-managed, free-ranged cow is able to turn the sunlight captured by

plants into condensed calories and protein with the aid of the

microorganisms in its gut. Sun > diverse plants > cow > human.

This in a larger ethical view looks much cleaner than the

fossil-fuel-soaked scheme of tractor-tilled field > irrigated soy

monoculture > tractor harvest > processing > tofu > shipping

> human.

While most present-day meat production is an ecologically foolish and

ethically wrong endeavor, happily this is changing, and there are

abundant examples of ecologically beneficial, pasture-based systems. The

fact is that most agroecologists agree that animals are integral parts

of truly sustainable agricultural systems. They are able to cycle

nutrients, aid in land management and convert sun to food in ways that

are nearly impossible for us to do without fossil fuel. If “ethical” is

defined as living in the most ecologically benign way, then in fairly

specific circumstances, of which each eater must educate himself, eating

meat is ethical; in fact NOT eating meat may be arguably unethical.

The issue of killing of a sentient being, however, lingers. To which

each individual human being must react by asking: Am I willing to divide

the world into that which I have deemed is worthy of being spared the

inevitable and that which is not worthy? Or is such a division

hopelessly artificial? A poem of Wislawa Szymborska’s, “In Praise of

Self-Deprecation,” comes to mind. It ends:

There is nothing more animal-like

than a clear conscience

on the third planet of the Sun.

For me, eating meat is ethical when one does three things. First, you

accept the biological reality that death begets life on this planet and

that all life (including us!) is really just solar energy temporarily stored in an impermanent form. Second, you combine this

realization with that cherished human trait of compassion and choose

ethically raised food, vegetable, grain and/or meat. And third, you give

thanks.

**

I can't say that I'm impressed, despite the thoughtfulness and nice writing. There's even a factual error in the essay:

"While most present-day meat production is an ecologically foolish and ethically wrong endeavor, happily this is changing, and there are abundant examples of ecologically beneficial, pasture-based systems.""This is changing" means we're going from "most is foolish and wrong" to "not the case that most is foolish and wrong". But there's no such trend. It takes far more than "abundant examples" of pasture-based animal farming to alter the big picture.

In fact, the general trend is toward even more animal farming being foolish and wrong. Populations are growing, affluence is increasing, affluent people are eating more meat, and we're running out of land. For all those reasons, the overall trend is toward an even bigger "most" being foolish and wrong.

It's one thing to eat meat you bought at Whole Foods--OK, it's better than McDonald's. It's another thing to think there's something exemplary and visionary about this, like you're leading the way to a better future. I don't think that can possibly be true, given diminishing available land.

For my money, the "manure" essays were better. They raised a very fundamental question about how plant and animal farming may be intertwined. If this is so, then you're complicit in killing animals whether you eat them or not. I think that's an interesting possibility.

Actually, I like my own effort on this topic. In a meat-free world, a staggering amount of the planet would be unavailable for food collection and production. I find that "food" for thought.

Must Read

If you read Brian Leiter, you will have read the funniest review on earth this morning. If you don't read him, today you must. The reviewer is Nina Strohminger. The book is The Meaning of Disgust, by Colin McGinn. She didn't like it. As a book reviews editor I'm just plain jealous. Why can't I get people to write reviews like this? (By the way, what's the magazine/journal? I can't tell from the pdf.)

5/3/12

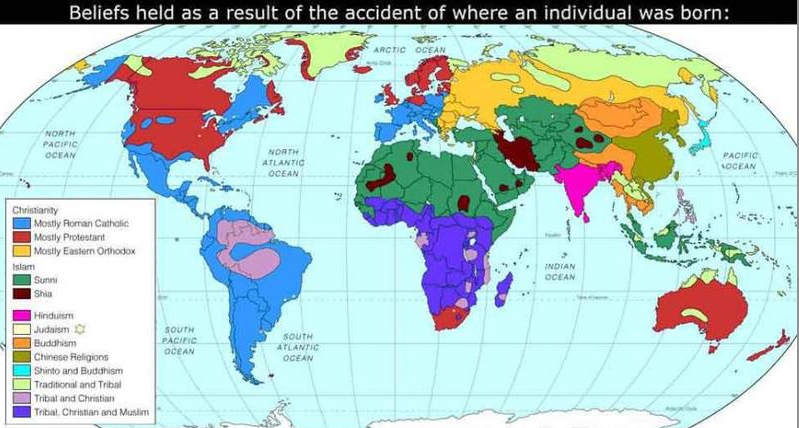

The Geography of Faith

Here's a reason to be a skeptic that holds up at first, but crumbles on reflection: religious beliefs depend on where a person lives. Via Jerry Coyne, here are two amusing maps:

If having a belief depends on where you live, the suspicion is that the belief is shaped by non-rational forces instead of being a consequence of the way the world is. We shouldn't take these kinds of beliefs too seriously, if at all.

And yet, and yet. The likelihood of believing in human rights, or equality for women, or same-sex marriage, or democracy ... all these beliefs would go on Map #1. They vary from place to place. Nevertheless, you could make a case that liberal democratic views on these matters are rooted in the way the world is. I'm not going to become a skeptic about women's equality, just because the folks in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia don't believe in women's equality. So why should anyone take sheer geographical variation as evidence that the tenets of some religion are false? Bad precedent!

If having a belief depends on where you live, the suspicion is that the belief is shaped by non-rational forces instead of being a consequence of the way the world is. We shouldn't take these kinds of beliefs too seriously, if at all.

And yet, and yet. The likelihood of believing in human rights, or equality for women, or same-sex marriage, or democracy ... all these beliefs would go on Map #1. They vary from place to place. Nevertheless, you could make a case that liberal democratic views on these matters are rooted in the way the world is. I'm not going to become a skeptic about women's equality, just because the folks in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia don't believe in women's equality. So why should anyone take sheer geographical variation as evidence that the tenets of some religion are false? Bad precedent!