And boy do they ever--turn animals into food. Here's a meal ordered by Mario Batali, another restaurant owner--five pork bellies, the "poutine" (huh?), two pig ears, two gnocchi, two sweetbreads, two quail, two fluke, two crispy rabbit legs, two pork ribs, two flat irons medium rare/rare, two veal breasts, "and no fuckin' vegetables."

What else does the restaurant serve? There's "lamb-tongue ravioli, lamb-heart paprikas, deviled lamb kidneys, veal brains grenobloise, " and recently the chefs have been experimenting with veal testicles. They seem to be a sensitive couple of guys. Here's one of them, waxing poetic about tofu--

"I had this weird thing last night" Dotolo said recently. What, did he have sex with his wife? No. "I was, like, eating tofu, and I was, like, thinking about how much it reminded me of, like, bone marrow and, like, brains and, like, that weird texture--like, soft, a little bit gelatinous. But the flavor of tofu is, like, so yelchth. I'll think about that now for, like, maybe a year befire I think about something to do with it. I think it'd be fuckin' hilarious to do tofu at Animal, just because it throws people off so much."

Hilarious! Or maybe even, like, fuckin' hilarous!

Earlier that day, I had read a post about food at Jerry Coyne's blog. It was an interesting reminder of my former self. That used to be me--the attraction to super-authentic food like barbecue, and szechuan cookery, the whole thing. In fact, I grew up eating the sort of stuff Mario had for dinner--the pigs ears, sweetbreads, quail, rabbit, everything. In "real world" terms, there was no difference. But there was a difference of attitude. We never relished the idea that we were turning real live animals into food. To tell the truth, the animals were "out of sight, out of mind." The only thing I couldn't get into was tongue. When you see a tongue lying on a plate it's impossible not to think of the mouth that used to house the tongue.

I am repulsed by Animal and it's ostentatious animal-to-food conversions, but feel a bit nostalgic about my former self's approach to food. Having food rules is particularly a problem when traveling. I will be visiting Italy soon, and hate to miss the local food. And yet, and yet. Here's Barbara King, talking about the problem of carnivorous Italy. And I'm just a vegetarian. A vegan would miss out on far more. Here's an ex-vegan talking about how the travel problem became a deal-breaker.

Bologna, Italy (known for its amazing food): I convinced my partner to go to the only vegetarian restaurant I could find out about in all of northwestern Italy. It was a total throwback to the 1970s. A tofu sausage rolling around on a plate with some boiled vegetables and alfalfa sprouts (this was listed as the hot dog option). I think the only thing that tasted good was the mustard.

Levanto, Italy: We were staying at a beautiful agriturismo olive farm up in the hills above the town. The woman who owned the farm came by our patio in the morning while I was having coffee to offer us fresh eggs, still warm from her hens. She had this lovely smile on her face and when I had to turn them down, her face just dropped and I felt like such an ungrateful asshole. We then walked to the horrid supermarket nearby to buy stuff for breakfast. How I couldn’t see the lunacy of this at the time completely baffles me now.

I wouldn't set foot in Animal. I'm not going back to being my former self, despite some nostalgia. But I don't think I want to become a person who turns down fresh eggs at an Italian olive farm. I'm not sure I can defend that, philosophically, but that's the way it is.

*

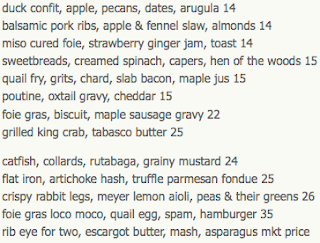

What? I surfed over to the Animal website, and couldn't believe my eyes.